If you’re reading this in the UK, Europe, America, or in fact, almost anywhere in the world, chances are you’ve never used a Chinese app. In fact, chances are you can’t even name one.

In a world where many of us rely on platforms like Facebook, Google and YouTube on a daily basis, it can be hard for us to imagine life without them. In China, however, a country once known for its cheap knock-offs and imitation products, this is reality. But it’s not a reality where citizens are deprived of basic social communication, as you might imagine. Far from it. Behind ‘The Great Firewall’ of China lies a parallel universe of industrial and scientific advancements that allows us to glimpse into an alternate vision of technology as we know it, as it could be and what it may yet become.

The China of today is a far cry from the unsettled and politically unstable country of the 1980’s. The economic and social changes that arose after the Mao era led to a huge proportion of the country’s younger generation becoming disenfranchised with the political elite, and worried about what the future may hold for them. Questions about the legitimacy of the ruling party, rumoured corruption amongst high ranking bureaucrats and unrest surrounding the reforms introduced by the communist party led to a social uprising, immortalised by the image of an unknown protestor standing defiantly in front of a column of tanks.

Borne out of these troubling times, however, grew a burgeoning economy, strong infrastructure and investment in technological and scientific research that has, behind closed doors, established China as a global superpower. ‘The Great Firewall’ has allowed the country to forge its own path in terms of technology, a path that appears to be absent of the platforms we’ve come to take for granted, such as Google, Twitter and eBay. But it’s not completely absent of them. Instead, China is taking a technological path that looks very similar, but is built very differently.

WeChat is creating a new way of life in China.

Copycat apps to Super-apps

The problem with trying to maintain what is, effectively, a shield around your country is that when websites and apps such as these become as big as they are, they traverse geographical borders, language barriers and cultural differences. It’s similar to when your neighbour gets a new car, or a new lawnmower. However much you don’t need a new car or lawnmower, you want one. You become envious. And however much the Chinese government attempted to shield its citizens from the western world, there was no hiding the emergence and increasing importance of platforms such as WhatsApp, PayPal and Uber, amongst many others.

The other problem is that in the western world we have laws and regulations around privacy and data protection that simply don’t exist in communist-led China. Platforms developed in the western world just wouldn’t work in China, as the government would be largely unable to monitor everything. The solution? Create ‘copycat apps’ that are incredibly similar to their western counterparts but approved and monitored by the Chinese government. For Google, there’s Baidu. For YouTube, Youku. For Twitter, Sina Weibo. And the list goes on. Huge swathes of the internet as we know it have been blocked by ‘The Great Firewall’, but an ever-growing number of imitation websites have emerged that enable the Chinese Government to control citizens’ access to the internet.

As these copycat apps began to emerge, app developers from Sydney to Stockholm dismissed them as imitations, or state-run ‘puppet apps’ that let the Chinese government keep tabs on its citizens. The path that these apps took, however, started to turn heads amongst the Silicon Valley hierarchy. The once derided Chinese apps were being seen as a glimpse of the future. They were starting to shed the moniker of ‘copycat app’. But most importantly, one of them was becoming the world’s first ‘Super-App’.

A numbers game

WeChat, or Weixin in Mandarin, is quickly becoming one of the most popular multi-purpose platforms, not just in China, but the world. Released in 2011 by Chinese internet giant Tencent, WeChat boasts nearly 800 million active monthly users, and its user base has been growing consistently every single quarter to date. To put into perspective, the population of China, at the time of writing, is 1.38 billion. That’s 60 active monthly users for every 100 people. Compared to its most notable rival, WhatsApp, the market penetration of WeChat is incredible – the app currently boasts average market usage figures of around 64% compared to WhatsApp’s 34% market penetration worldwide.

But to those of us more familiar with its western counterparts, it’s not the figures surrounding WeChat’s usage that are interesting. It’s the actual embodiment of the app.

It's safe to say that the most ardent of technophiles will probably have at least 100 apps on their smartphone. Speaking as one of them, I am not ashamed to say that I currently have a grand total of 127 apps installed on my own device. I have Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Telegram, Skype, Google Hangouts and Duo installed to cover my instant messaging needs, and that’s excluding my text messaging apps. I have Uber, Lyft, Citymapper, Waze, Tripadvisor, AirBnB and Skyscanner, all installed for when my inner globetrotter takes over. Likewise, when I’m feeling a bit peckish, I turn to one of Deliveroo, Just Eat, OpenTable, Zomato, Yelp or Urbanspoon. That’s 19 apps to cover three essential functions. WeChat? It’s got them all covered. For WeChat isn’t just the messaging app that many assume it to be. It’s a whole lot more.

Off the bat, WeChat lets users do everything you’d

expect it to – instant messaging, sharing life events and

chatting to family members. But its feature list extends far beyond custom

emojis and profile pictures. WeChat allows you to arrange a catch-up with a

friend, pre-order food from a restaurant, book a taxi to the restaurant, get

directions on foot, pay for the meal (or send your friend the money), check

movie times and book tickets, and also buy that coat that you’ve been after for

ages that has just been put on sale. All without hitting the home button.

WeChat users benefit from the vast array of features available through the platform (Image courtesy of WeChat)

On the surface, this sounds amazing, at least for the user. Not only does being able to use one platform to complete various different tasks throughout the day save time, it also makes using your phone that little bit easier and provides a solution to the inevitable ‘curse of the forgotten password’. But whilst the main benefit may appear to be the ease of use for the user, WeChat is actually one of the world’s most comprehensive and intelligent data-gathering tools. And yep, you’ve guessed it – this is a marketer’s dream.

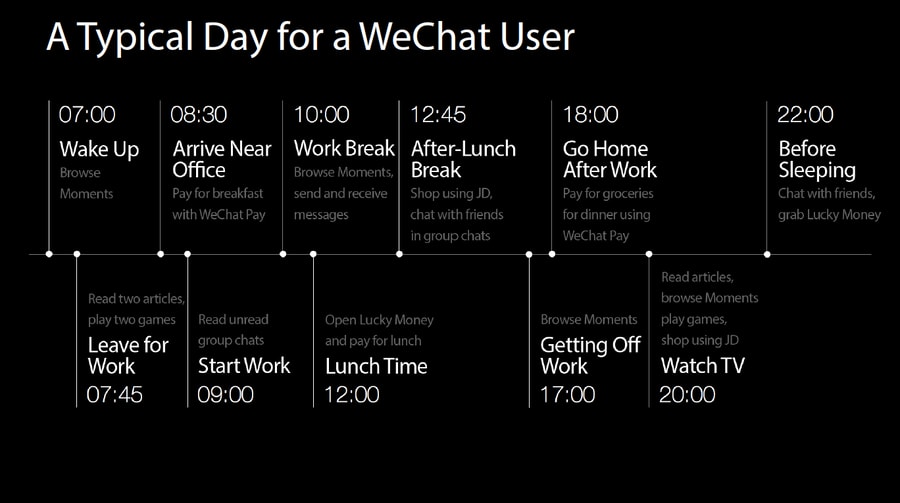

The possibilities for brand-to-consumer engagement on WeChat are almost unparalleled anywhere else in the world, and this is almost entirely due to the way the app manifests itself in as many aspects of daily life as possible. By knowing a person’s current location and when they usually have dinner, all in one app, fast-food brands can hyper-accurately target consumers when they’re most inclined to purchase. And by tapping into the app’s data on payments and money transfers, marketers can get a good idea of when, where, how and why users spend their money, before using this to hyper-accurately target their audience when they’re most likely to buy.

Whilst this would be an issue for many privacy-conscious consumers, another aspect of the app might provide more cause for concern. Whereas WhatsApp maintains a relatively strong stance on free speech (as long as you don’t mind its owners, Facebook, using your chat logs to target its advertising), WeChat, under the jurisdiction of the Chinese government, goes a step (or more aptly, a staircase) further. Censorship, topic restriction and reports of accounts being banned for talking about certain subject matter are rife, something that was recently brought to light by former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick. As well as claiming that the US-based ride-sharing app had had all of its accounts blocked on the Chinese app – which incidentally provides financial backing to one of Uber’s rivals, DiDi – Kalanick also alleged that positive news about Uber had been censored out of public view, while negative stories about the company were promoted. It came shortly after large-scale pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, during which WeChat users were seemingly unable to see photos of the protest posted by users with Hong Kong phone numbers.

Whilst unproven, both Kalanick’s claims and the furore surrounding the censorship of the demonstrations support the growing number of voices raised in protest at the attempts of Tencent and the Chinese government to seemingly control what people see.

Yet despite these concerns, what shouldn’t be overlooked is the technological power that has made a super-app such as WeChat possible. Imagine it in the hands of a western audience and the future looks very exciting indeed.

The future of business, simplified

WeChat shows us the future of tech, where convenience and connectivity come together in one seamless experience. While its unique environment may not be for everyone, the idea of simplifying daily tasks and business needs on a single platform is something we can all learn from.

If you’re looking to streamline your business growth with fast, flexible funding – without the hassle – an SME loan from Fleximize can help you get there.

These cookies are set by a range of social media services that we have added to the site to enable you to share our content with your friends and networks. They are capable of tracking your browser across other sites and building up a profile of your interests. This may impact the content and messages you see on other websites you visit.

If you do not allow these cookies you may not be able to use or see these sharing tools.